Jamil Al-Amin, Fiery Civil Rights Leader Once Known as H. Rap Brown, Dies at 82 in Federal Prison

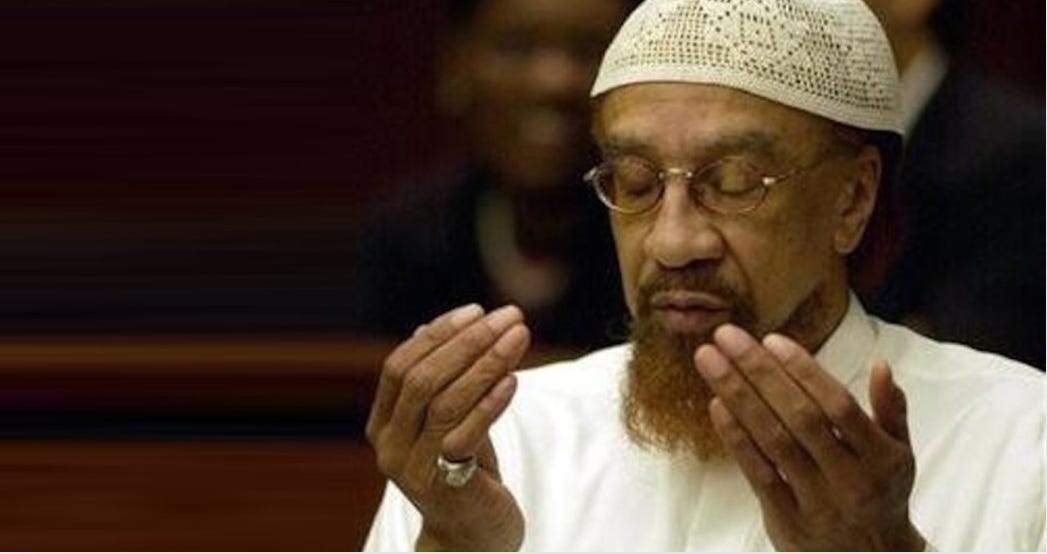

The Black Power activist Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, who gained fame as H. Rap Brown during the 1960s and later became a respected Muslim imam, passed away at the Federal Bureau of Prisons hospital in Butner, North Carolina, on Sunday. The Washington Informer reported that Al-Amin died at 82 years old while fighting multiple myeloma, which is a blood cancer. The passing of Al-Amin brings closure to his life, which included civil rights activism, urban activism, and forty years of prison time.

From Civil Rights Firebrand to Federal Target

Al-Amin, born Hubert Geroid Brown on October 4, 1943, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, became chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in May 1967, succeeding Stokely Carmichael. Upon taking leadership, he immediately advocated for removing the word “nonviolent” from the organization’s name, successfully changing it to the Student National Coordinating Committee.

After the deaths of two of his comrades in a bombing in 1970, H. Rap Brown went underground and, about a year later, reports circulated that he was leading a cell in New York City specifically targeting businesses and individuals involved in drug sales within African American communities. His wife, attorney Karima Al-Amin, described this effort as the “H. Rap Brown Anti-Dope Campaign,” highlighting his commitment to confronting the drug trade and its impact on Black neighborhoods. For 19 months, Brown evaded capture before being apprehended in October 1971, following what authorities labeled an “armed robbery” incident. He was attempting to clean up New York City’s drug problem, and his trial was defended by prominent civil rights attorneys William Kunstler and Howard Moore.

Brown’s activism began earlier as a student organizer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), where he worked alongside Martin Luther King Jr. on desegregation and voter registration drives, notably serving as SNCC’s Director of Voter Registration for Alabama in 1966. His early work focused on nonviolent civil rights. The legacy of H. Rap Brown also extends to popular culture, as rap music is widely believed to have been named after him, reflecting his enduring influence on both activism and music.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover targeted Al-Amin through the agency’s COINTELPRO program, ordering agents in secret memos to arrest him “on every possible charge until they could no longer make bail,” according to later-released documents. Al-Amin went underground in 1970, spending 18 months on the FBI’s Most Wanted list before resurfacing in October 1971 following a shootout with New York City police. He was convicted of robbery and assault with a deadly weapon, serving five years at Attica State Prison in New York.

Transformation and Community Leadership

While imprisoned, Al-Amin converted to Islam and adopted his new name. After his release, he settled in Atlanta’s West End neighborhood, where he established himself as a community leader. He organized youth activities and worked to combat street crime and drug trafficking, earning recognition as “a pillar of the Muslim community” among local Islamic leaders. According to the New York Times, he lived there with his wife and their two children, Ali and Kairi.

Despite his community work, law enforcement continued monitoring him intensively. Following the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, the FBI deployed informants to infiltrate Al-Amin’s mosque and assisted local authorities in investigating alleged connections to terrorist plots, bank robberies, and multiple homicides in Atlanta between 1990 and 1996, according to police records revealed by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. No connections were ultimately established.

The Fatal Shooting and Controversial Conviction

On March 16, 2000, Fulton County Deputy Sheriff Ricky Kinchen and his partner Aldranon English approached Al-Amin’s store to serve an arrest warrant for a missed court appearance related to a minor traffic offense. Both deputies were shot; Kinchen died from his wounds, while English survived despite multiple gunshot injuries. English identified Al-Amin as the shooter from a hospital bed photograph that evening, an account corroborated by a blood trail from the scene, according to prosecutors. Al-Amin was apprehended four days later at a friend’s residence in Alabama without visible injuries to explain the blood evidence.

In March 2002, Al-Amin was convicted on 13 counts, including murder, and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. The verdict remains deeply controversial among supporters and civil rights advocates. The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) and other organizations have argued that the prosecution was flawed, pointing to procedural irregularities, unreliable evidence, and a sworn confession from federal inmate Otis Jackson, who has repeatedly claimed responsibility for the shooting. “He was both a hero and a victim of injustice,” said CAIR Executive Director Nihad Awad, calling on authorities to reopen the case and clear his record.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

Al-Amin spent his final years in federal custody, transferred from Georgia’s prison system to facilities in Colorado’s supermax prison before moving to the federal medical center in North Carolina. His son, Kairi Al-Amin, repeatedly raised alarms about his father’s declining health and inadequate medical treatment in prison. Upon learning of his father’s death, Kairi wrote on social media: “They don’t have him anymore. He’s free”. Imam Omar Suleiman added: “From prison to paradise, God willing. He never lost his dignity, his voice never shook”.

Al-Amin’s legacy remains divisive. To supporters, he represents a fearless advocate who challenged systemic racism and later transformed communities through faith-based activism. Critics view him as a violent radical whose rhetoric incited destruction. The debate over his 2002 conviction continues, with the Innocence Project securing hundreds of pages of court documents as recently as last year. As tributes spread across the nation, many supporters emphasized that while he has passed, the campaign to restore his name continues. His 1969 autobiography, “Die Nigger Die!,” written in provocative style and drawing on revolutionary theorists like Frantz Fanon, remains a testament to his uncompromising revolutionary-nationalist politics centered on anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism.